Foreword: Stories of Beirut: A Grandchild’s Reflections of “Home” is a collection of four short stories describing the experiences of the Lebanese diaspora. As a diaspora, our connection to Beirut is complex and often difficult to describe. We are neither here nor there. Sometimes we want to let go of our homeland and move on from the traumas of our past. But letting go is never really possible. In a single moment, the explosion in Beirut on August 4th, 2020 unleashed years of survivor’s guilt that we had suppressed for so long. In these stories, we show that it is impossible to let go of Beirut because Beirut is not a place. Beirut is the people we love. Beirut is the people we left behind in pursuit of an alternative future.

I am the grandchild of Amira, Izzat, Raheel, and Saïd.

Home is not a place.

Home is a people.

Borders are not fixed.

There are no borders.

My body is here, but my mind and soul are there.

Teta Amira’s flowers weave in and out of the balcony railings to find space among the other plants. They sit defiantly above the busy street in Beirut. I was out on the balcony, playing with my toy car. I would roll the wheels on the concrete half-wall that supported the black iron rails. The cars honked, and I honked back, at least in my mind, adding to the orchestra of chaos.

Then Amira walked out with scissors in her hand, “Habibi, I’m going to pluck gardenias. Would you like to help me?” I nodded my head yes and placed my little car on the ground, the gear in park.

“Yalla, let’s get the ones that have bloomed,” she said. She handed me a pair of new gardening scissors, leaving herself an old rusted set that looked as if they couldn’t cut through the air. I found a pretty one, I squeezed the scissors tightly, but they couldn’t cut the stem. I looked up at Amira. I could tell she’s a short woman, even for an adult. She’s full and her hair a bright silver in two small braids. Amira took her rusted scissors, found a flower and the stem cut! One by one, the flowers leaped off their stems into her petite hands. It was as if they knew who she was and were desperate to go with her.

I tried to cut another stem. It resisted me, so I grabbed it, and a thorn pricked my finger. “ah!” I exclaimed. Amira looked down at me, “what Habibi? Oh, you pricked your finger! Don’t worry that used to happen to me all the time.“

“Teta, how do you take care of the flowers so well?” I asked her, looking at my finger. She chuckled. “Habibi, you just need to take care of them.” She gave me one of the gardenias. “This one is nice. Go on, smell it.” I breathed in the scent, and it quieted everything around me, the traffic was gone, the city was gone. It was even as if the prick in my finger disappeared. She gave me a kiss on my forehead and headed back inside, where she placed the flowers in small little glasses around the house. I picked up my toy car, putting the flower inside it. I headed off the balcony and stuffed the car in my backpack by the window and then went to have tea with Amira before heading off to the airport with mom.

“Baba, don’t forget your school bag” Izzat pointed to the small backpack with an image of Mickey Mouse on it. I tied my shoelaces, grabbed the Mickey Mouse bag, and then took Izzat’s hand as we walked out of the door.

He looked down at my curly hair and smiled. “Where’s your pipe?” I asked him. Izzat laughed. “In my pocket.” I could smell it, the scent of Captain Black’s tobacco. He always carried that tobacco with him and used it to fill his pipe. “You smell like that black stuff in your pocket,” I laughed. My grandfather’s pipe fascinated me. The other day, I gave it a couple puffs when no one was looking. To my disappointment, nothing happened.

We walked out of the house together and waited by the road like we always did. The school bus would arrive soon. He patted my hair softly and squeezed my small hand. This would be the last time that he would drop me off at the bus stop before I left Beirut that evening. I looked at the ground, trying to hide my face with my hair, as tears started to leak through the corners of my eyes. I was not sure when I’d come back to see him. But I knew that I had to leave Beirut for a while. “Jedo,” I exhaled, trying to even out my voice, “what if they don’t like me at the new school? What do I do?”

He smiled at me affectionately and bent down a little lower so that my face was almost at level with his. He replied: “Jedo, I want you to know…” he wiped the tear falling down my cheek “every time you get on a bus, I’ll be thinking of you. And you can think of me too. That way, even if we’re apart, it’s like I’m walking with you to the bus.” I hugged him tightly. I loved his idea, but I was also a little concerned about how it would work: “But Jedo…how will you always know when I’m about to get on a bus?” Izzat assured me: “Habibti, I am always thinking of you. You can always meet me in your mind, every time you get on a bus, I’ll be there” he pointed to my little forehead.

The school bus arrived. The doors swung open, and I lunged up onto the bus’s platform with my short legs. “Bye, Jedo!” Izzat laughed at my childish excitement. “Bye, habibti, Allah ma3ik*.” I sat down inside the bus and hugged my Mickey Mouse bag close to my chest, thinking of our special promise.

“Shit.” I panted. I just ran through two blocks and snowy streets to get to the terminal, but I still missed the bus. I collapsed onto the cold metal bench underneath me. I needed a hot shower. I needed this day to end. It was just one of those days – just a shitty day.

In the corner, I saw a white wrapper on the ground. It flitted around as people opened and closed doors in the bus terminal. The wrapper looked oddly familiar to me. I knew I had seen it before. But where? I pushed my hand against the armrest to move forward and looked at the wrapper closely, straining my eyes. For the first time in years, I saw it again – a small black ship printed on the wrapper with cursive text underneath:

“Captain Black: Pipe Tobacco.” I stared at the wrapper for what felt like forever, frozen in my seat.

Years had passed.

Many buses had come and gone.

And I forgot to meet him.

*”Allah ma3ik” means “God be with you” in Arabic.

I think of her from time to time. I have a picture of her on my nightstand. I pass by it every day. Sometimes I forget that it’s there. I get distracted easily. Time runs, it sprints all day long and pulls me along without my consent. Sometimes I remember to look at her picture. When I do, I feel like I can resist Time’s momentum, just for a second. The photo was taken somewhere in Lebanon’s mountains, right in front of a beautiful, antiquated church. It overlooked the Mediterranean Sea. I picked up the frame and brought it closer to my face. I closed my eyes and tried to remember. It was a long time ago.

We were together that day, her and I, surrounded by orchards, olive trees, and cedars. I still remember the rising pressure in my ears as we drove up the mountain towards the church. It was surrounded by a stunning courtyard with marble pathways. The main entrance was flanked by cedars and flora on either side. The smell of pine was infused in the earth and the air. I ran around the courtyard restlessly, scurrying on little legs to look at vividly coloured flowers planted along the path. To my parents’ dismay, I didn’t care if I fell face forward or stained my white dress. As a mischievous child with somewhat reckless pursuits, I had to touch and see everything.

I was looking at a yellow tulip when she knelt down and kissed my forehead. She pointed at the different flowers and told me their names. When the church bells began to toll, she stood up and made her way towards the large wooden doors that guarded the church’s entrance.

Curiosity told me to follow her. I heard my mother call my name, but I didn’t turn back. I ran along the marble path and made it just in time to enter the church with her. She noticed my presence when I reached up to hold her hand. Smiling down at me, she patted my head softly. I followed her inside. The high ceiling was sculpted with soft arches. The walls were a pristine white, bounded by golden threads along the edges. The windows were majestic works of art, stained with powerful imagery and captivating colours. They stretched from the floor to the ceiling and filled the space with pure bright light.

We made our way into one of the rows at the back of the hall. A priest cloaked in a white robe stood at the very front and addressed the seated crowd. She held my hand and placed it on her lap. As she closed her eyes and listened to the priest speak, I gazed at the golden bracelet around her wrist. It was a simple piece, a thin band of gold metal with flowers engraved all over it. Whenever I sat next to her, I would try to pull the bracelet off her wrist, but it never moved passed the lower part of her thumb. It fascinated me that she had gotten a golden bracelet stuck around her wrist for so long. She didn’t seem to mind, though. If anything, she was amused by my persistent attempts to remove it.

It was the first time I had ever been to a church. As a seven-year-old, I knew that I wasn’t born a Christian; I knew she was, though – my grandmother. Sometimes, I heard other adults say that people like me shouldn’t go into churches. I didn’t understand what they meant. Why did they say that? As I sat there next to her, I didn’t feel like I had done anything wrong. I traced the flowers on her golden bracelet with my finger and let my feet dangle above the floor.

The bells of Time began to toll, pulling me out of the past and into the present. Usual momentum resumed. My thumb rubbed the side of the picture frame. I was particularly amused by my seven-year-old self and her thoughts in the church that day. Her questions were innocent and fearless of consequence.

“Dad … why does this book have my name on it?“

I stood on the stairs in my pirate pajamas, holding the beige paper book.

“No, Habibi!” he laughed, “this is jedo Saïd’s book, my dad.”

I walked over to dad and sat on his lap, putting the book in mine.

“He wrote a book?” I asked.

“Yes, Habibi, you see it’s about Beirut.”

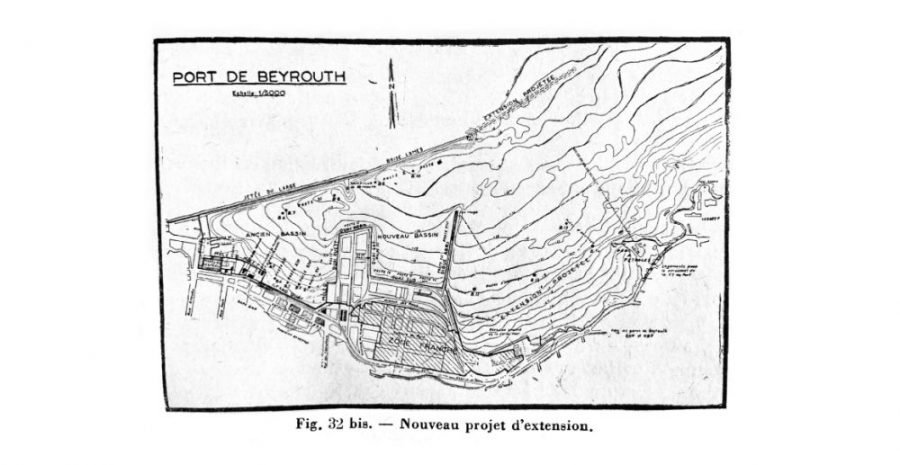

The cover was speckled, the way old parchment ages, but the black ink was still intense, Geographie Humaine de Beyrouth.

“What does it say, baba?” my dad held the book in my lap and started to flip through the pages. I looked closely at it as if I had just discovered a treasure of the deep. “You know, jedo drew these,” my dad said, pointing at a series of drawings. I looked up at him in amazement. I grabbed the book in my small hands and stared at the sketches, running my fingers on his strokes of Beirut. I felt my dad’s arms close in tighter around me.

“Baba, why did he write a book about Beirut?” I asked.

“Habibi, jedo is one of the first Lebanese to graduate with a doctorate from the Sorbonne, he was a doctor of geography.”

“But why, Beirut?” I pestered.

“Because he loved Beirut.“

I flipped through the pages slowly. The book was in French, and I didn’t know French.

“Baba … what happened to jedo?“

My dad’s arms tensed up. He lifted me and stood me up. Me still holding the book in my hands, I turned and looked at him. He touched my cheek, “Yalla, time for bed, Habibi.”

I took the book with me to bed, sitting on top of my duvet with my side light on. Flipping through it, I discovered a bar-chart Saïd drew, where the bars are made of ships with a tiny little lighthouse on the edge. I began to imagine how he probably drew it for amusement and started picturing how he would have laughed. How did he sound? Was his voice deep?

I flipped the page and saw his drawing of the Port. Everything was done with the care of an academic; accurate and meticulous. Probably a deep voice, I thought. Then I found a drawing that flipped out. I laid it flat, pressing out the waves of my sea-blue sheets. I moved my ship-like bedside table closer and pulled the light in. It was a map of Beirut, all the buildings outlined, the roads sharp, and everything was labeled. Was he an explorer? A treasure hunter? Too many maps for a doctor…

I stared at the roads, at the knowledge. He probably knew where all the treasure was buried, I think he would have shown me where it was. We would have toured the city. He would teach me everything about it. I guess he would have shown me what it means to be proud. He would have shown me what it means to be from Beirut.

I am the grandchild of Beirut.

Beirut is not a place.

Beirut is a people.

Borders are not fixed.

There are no borders.

My body is here, but my mind and soul are there.